Along graceful streets shaded by sycamores and magnolias, residents wake up early to beat the heat on this summer Sunday. Some head out for runs and bike rides, winding their way through a neighborhood with homes dating to as early as the 1920s and built in a mix of period styles: Tudor Revival, Spanish Colonial and American Colonial, as well as a smattering of postwar ranch houses.

Unlike other tony enclaves of Southern California, the houses in Toluca Lake don’t retreat from the street, nor do they hunker down fortress-like behind towering walls and hedges. First and foremost, Toluca Lake is a real neighborhood. There are women pruning rosebushes while kids play in circular driveways.

Toluca Lake does have its hidden places. Drawn to the neighborhood for glimpses of Bob Hope’s former five-acre estate and the home where famed aviator Amelia Earhart lived before leaving on her fateful 1937 round-the-world flight, the few tourists who find their way to Toluca Lake don’t see the golfers teeing off on the historic Lakeside Golf Club course. Or those lucky few residents sipping their morning coffee while gazing out from their docks along the lake.

Yes, there is a Toluca Lake in Toluca Lake (more on that later).

Other residents stroll through the neighborhood, bound for breakfast along Riverside Drive, the main drag that runs between Toluca Lake’s different sections. Some opt for stylish Sweetsalt, where the interior, with its plank floors, wainscoting and cool grays, combines the rustic and contemporary. Others go retro at Patys Restaurant, a Toluca Lake landmark since 1960.

With so many longtime residents in Toluca Lake, plenty of locals still remember the restaurant by its original name, Gabys. Legend has it that when a former owner bought Gabys, it was cheaper to change only two letters rather than the entire sign. So Gabys begat Patys.

By any name, the restaurant is jammed with a diverse crowd of diners. Nobody is especially concerned about a missing T, much less the sign’s AWOL apostrophe, not with stacks of pancakes and French toast to be devoured. Proudly displayed beneath transparent covers on chrome stands, towering layer cakes line the counter, while pies fill a case across from a wall covered by signed celebrity photographs. A few flesh-and-blood celebs are tucked away in the booths, too — but in a community where stars have been part of the landscape since the 1920s, everybody leaves them alone. Because from the silent era to the age of selfies, Toluca Lake is a place that’s more about “live and let live” than “see and be seen.”

A Stealth Neighborhood

The truth is that Toluca Lake may be the least-known neighborhood filled with world-famous people anywhere on the planet. Even in Los Angeles, plenty of people don’t know it exists; of those who do, many couldn’t find it on a map.

Part of the reason for Toluca Lake’s stealth status is that it’s not really on the way to anywhere. Largely separate from the main San Fernando Valley road grid, the neighborhood dead-ends at the golf course, and beyond it the Los Angeles River. So outsiders aren’t likely to accidentally stumble upon Toluca Lake, while harried commuters directed by Waze onto Riverside Drive from the 134 Freeway probably never realize that a classic residential neighborhood begins only one block south.

“It’s a tiny little place, and those people who know about Toluca Lake realize that it’s a real gem,” says Kevin Roderick, founder and editor of the LA Observed website and author of The San Fernando Valley: America’s Suburb. “But for others, it’s like, ‘Where’s that?’ I had lived in the Valley for a long time before I ever found the neighborhood. You can easily miss it.”

While other early Valley movie colonies have largely been subsumed within the sprawl, Toluca Lake has managed to maintain its sense of separateness. “A little bit of Beverly Hills in the Valley” is the way Roderick describes it, though while Beverly Hills has evolved into a brand, Toluca Lake remains, first and foremost, a community.

“It’s a great family location,” Roderick says. “These are not party houses or a place for some aging actor who wants to live by himself on a hilltop. It’s a quiet, suburban family neighborhood — Little League and Girl Scout cookies. No one goes to Toluca Lake to be ostentatious.”

What’s now typically described as “Toluca Lake” actually spreads from Los Angeles into Burbank, though the heart of the neighborhood within the original 1923 subdivision has clear borders: the river on the south and Camarillo Street to the north, Clybourn Avenue on the east and Cahuenga Boulevard to the west. If, in some ways, Toluca Lake is a state of mind, the people who know the neighborhood best think of it as a geographically defined place.

As a Chamber of Commerce representative told the Los Angeles Times in 1980, “Those who live within our boundaries know they do, and those who don’t wish they did.”

Discovering Toluca Lake

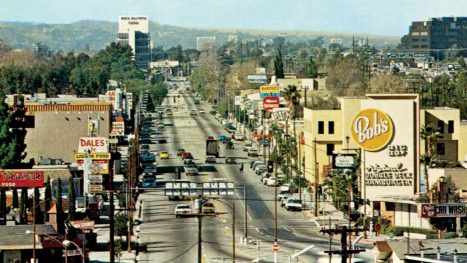

I can speak from experience: One evening after moving to Los Angeles way back in my late 20s, I was driving down Hollywood Way from the Burbank Airport. I missed the freeway entrance, then turned right on Riverside Drive, where I caught my first glimpse of the iconic Bob’s Big Boy restaurant, aglow at dusk and with vintage cars revving in its parking lot. A postwar classic, the 1949 Streamline Moderne masterpiece by Wayne McAllister to this day hosts gatherings of custom hot rods and born-in-Detroit V-8 muscle, bringing alive a vision of an earlier Los Angeles.

Farther west, Patys was still Gabys, and across the way, I noticed a one-of-a-kind bank building at Mariota Avenue (now a Wells Fargo), which was designed in the early 1980s by none other than Frank Gehry. Though the neighborhood isn’t generally known for its modern architecture, I later learned that a sleek midcentury home on Toluca Lake Avenue is actually Case Study House #1, part of the influential program launched by Arts and Architecture magazine to showcase new approaches to residential design.

The walkable heart of the village proved to this SoCal newcomer that there was indeed more to L.A. than mini-malls. Toluca Lake intrigued me and I decided to look for a place here. Alas, with the lakeside homes beyond my wildest dreams of screenwriting riches and even apartments within the most loosely defined boundaries of Greater Toluca Lake-adjacent still outside my limited budget, I wasn’t destined to join the lucky ranks of Tolucans.

Even so, I never lost my curiosity about the neighborhood, especially the golden era when Toluca Lake reigned as one of Southern California’s most exclusive enclaves.

Richard Arlen, who costarred in Wings, winner of the first Academy Award for Best Picture, was one of Toluca Lake’s first residents and its honorary mayor. The Lakeside golf course, designed in 1924 by Max Behr (considered one of the most innovative course architects of his time), was the initial draw for Arlen. But Arlen eventually saw the potential of Toluca Lake as a place to live and built his own home, then touted the area to his Hollywood friends.

As recalled in a 1932 newspaper article about Arlen’s early days in Toluca Lake, “Languid eucalyptus trees lifted their pungent leaves in lazy greeting, peppers wept their red teardrops, willows leaned gracefully against the soft breeze … Out there — so Dick raved with the zeal of a fanatic — you could paddle your own canoe, hoe your own row of ’tatoes, do what you pleased.”

Apparently that was true. According to a 1974 column by legendary sports columnist Jim Murray, when one afternoon Arlen landed his light plane on the course’s ninth green, club members joked that “it was the first thing he landed on the green in regulation all year.”

Drawn not only by the sylvan setting but easy access to the nearby Universal and Warner Bros. studios, more stars moved into the area. Bette Davis built a Tudor Revival and W.C. Fields battled the swans on the lake — and sometimes the roadside trees during drunken drives back to his house. Dorothy Lamour, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope all took the road to Toluca Lake, though for Crosby, reality sometimes intruded on this in-city paradise.

In 1939, a $100,000 kidnapping plot targeting Crosby’s children was narrowly thwarted. Then in 1943, the “White Christmas” singer’s holiday turned decidedly black. Faulty wiring torched the family Christmas tree, setting off a fire that almost completely destroyed Crosby’s colonial mansion on Camarillo Street, as well as most of his possessions. Among the items saved: a prized original manuscript of the song “Dixie” and also Crosby’s golf clubs. He played Bel-Air the next day.

Nor was Crosby the only crooner to battle a conflagration at Toluca Lake. Frank Sinatra and his family moved to a house along the lake on Valley Spring Lane in the 1940s. His daughter Nancy recalled that one summer the family hosted a Fourth of July show for the community, with Sinatra taking charge of the fireworks. She wrote that her father rowed a raft laden with fireworks out into the lake, then lit the first pinwheel, whose errant sparks set off a chain reaction while “The Stars and Stripes Forever” played over the speakers. Nancy panicked as Frank disappeared behind clouds of smoke, only to emerge from the lake as the neighbors fought to douse the flames.

Moving Ahead While Celebrating the Past

Running for less than a mile through Toluca Lake, Forman Avenue is neither one of L.A.’s longer nor more famous streets. But the avenue holds a place of honor here because it was named for General Charles Forman, a prominent early Angeleno. It was his former ranch (including the natural spring-fed pond that became today’s Toluca Lake) that was subdivided to create the neighborhood.

Indirectly, Forman also gave the community its name. As the story goes, Forman had dubbed a larger valley area that now encompasses North Hollywood as Toluca. Forman said Toluca translated as “fertile valley” in the Paiute Indian language, though there’s also a city named Toluca in Mexico, while the great cultural anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber, who specialized in western Native American cultures, believed the name probably came from a tribe living near San Juan Capistrano.

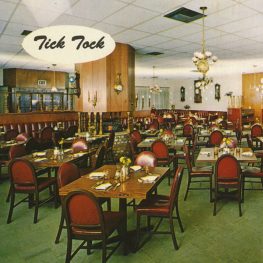

The transformation of the walnut and peach groves at Forman’s ranch into an exclusive residential hideaway was a swift one. And as much as Toluca Lake venerates the past, the community isn’t immune to change. Classic Riverside Drive restaurants such as the Tick Tock Toluca and Alfonse’s (where in 1967 the Chateaubriand for two would set you back a cool 12 bucks) are long gone. More recently, the curtain closed on the beloved Papoo’s Hot Dog Show after 62 years as the restaurant gave way to a branch of Umami Burger.

But change doesn’t mean a complete break from the past in Toluca Lake, certainly not at Forman’s Whiskey Tavern, the woodsy, lodge-like watering hole that opened in 2015 in the onetime home of The Money Tree, a classic jazz spot. The tavern, of course, is named for Charles Forman, says Ludwig Chavez, a partner in the restaurant and a self-described “Valley kid” with long Toluca Lake ties.

“The neighborhood has become younger and more contemporary, though it’s still very traditional,” he says. “We’re seeing a lot more homeowners in their 40s and more baby strollers as a new generation moves in. Along with the studio people, neighborhood residents are walking over here, especially on the weekends. Because we’re a proper pub, not a TMZ site. You don’t have to deal with a bunch of flashbulbs here.”

That’s a vibe that Toluca Lake’s low-key residents certainly appreciate. And the historic name didn’t escape notice either. Chavez says that during the restaurant’s build-out phase, he got into a conversation with a longtime Toluca Lake resident who is probably in his mid-80s.

“When I told him we were going with the name Forman’s, he was absolutely thrilled,” says Chavez. “I’ve just never seen a man’s eyes light up quite like that.”

By Los Angeles standards, the days of Charles Forman are ancient history. A century is a long time in these parts, and it’s tough to picture Toluca Lake as a haven of orchards near the Los Angeles River. But the golden age of Hope and Crosby and the other stars still feels close enough to touch. There are enough surviving reminders (Hope’s estate can be yours, by the way, for $22 million) that it’s possible to imagine the era of fly-fishing derbies and impromptu sailing regattas on the lake.

The tug of nostalgia is irresistible in Toluca Lake. Yet whenever I come back, I’m also eager to see what’s new, to experience the living, evolving community that’s rooted in old Hollywood but always moving forward. Because in Toluca Lake, there’s an inescapable sense that, as Sinatra once sang, the best is yet to come.