Tens of thousands of people joined Universal Moving Picture Company President Carl Laemmle on March 15, 1915, to celebrate the opening day of his grandiose, state-of-the-art new film studio in the San Fernando Valley called Universal City. In addition to special events like an aerial flyover, rodeo and stunt show, attendees enjoyed the opportunity to witness actual filming of motion pictures on a studio lot. As Universal City celebrates its 105th anniversary this year, it remains one of the Valley’s largest employers and one of the area’s most popular tourist attractions.

German immigrant Laemmle arrived in the United States in 1884 at the age of 17, settling in Chicago. After more than 20 years of struggle, he and Robert Cochrane invested modest nest eggs in a nickelodeon in 1906 before opening Laemmle Film Service to rent prints to other exhibitors. Sensing that Thomas Edison intended his Motion Picture Patents Company to control the film business, the wily Laemmle formed Independent Moving Pictures Company (IMP) in 1909 to produce his own movies. The company gained legitimacy in 1910 when it signed rising star Mary Pickford to an exclusive contract.

On June 8, 1912, budding moguls Laemmle and Cochrane formed the Universal Moving Picture Company, merging IMP with Pat Power’s Picture Plays, David Horsley’s Nestor Film Company, Adam Kessel and Charles Bauman’s New York Motion Picture Company, Champion Film Company and the Rex Motion Picture Masterpiece Company. Historian Anthony Slide states in his book Historical Dictionary of the Motion Picture Industry that the new conglomerate’s name was suggested by a board member after seeing a truck emblazoned with the name “Universal Pipe Fittings” drive by.

While several of Universal’s member companies shot out of studios in Fort Lee, New Jersey, some already operated out of the Los Angeles area. The NYMPC produced its Bison westerns at an Edendale Studio, and Nestor shot films outside a converted tavern at Sunset and Gower. To save money, Laemmle decided to consolidate many divisions in California.

In August 1912, Laemmle’s Universal leased the Providencia–Oak Crest Ranch at what is now Forest Lawn Hollywood Hills as a production facility, building outdoor sets, stages and an Indian village, as well as permanent housing for 65 families. That December, the company invited local and state politicians, rival photoplayers and the general public to celebrate its opening.

The studio executives worked out a deal with Los Angeles County to create a quasi-legal community named “Universal City” at the ranch on July 10, 1913, which they described as the “Most Unusual City in the World” in trade ads. A 1913 Motion Picture Story magazine article reported, “Cucumbers, tomatoes, green peas, asparagus, strawberries, and films are some of the crops of Universal City.” In September, Universal offered its first studio tour, organizing bus excursions from Los Angeles.

Intending to build the world’s most elaborate film studio, Universal attempted to buy out the entire Providencia Ranch but found itself rebuffed. Laemmle bought a full-page advertisement in the February 19, 1914, Los Angeles Times, noting the company spent $1 million annually to produce films and offered employment to hundreds, asking what inducements cities would offer in exchange for studio construction. The ad further stated, “We want a ranch of 600 to 1,200 acres on which to produce moving pictures.”

Motion Picture News reported on March 7, 1914, that Universal spent $160,000 to purchase the Taylor, Boag, Hershey and Davis ranches located within 200 feet of the streetcar line and adjacent to the Los Angeles River, across the road from the Campo de Cahuenga, where the peace treaty with Mexico that paved the way for California and the West to become part of the U.S. had been signed in 1847.

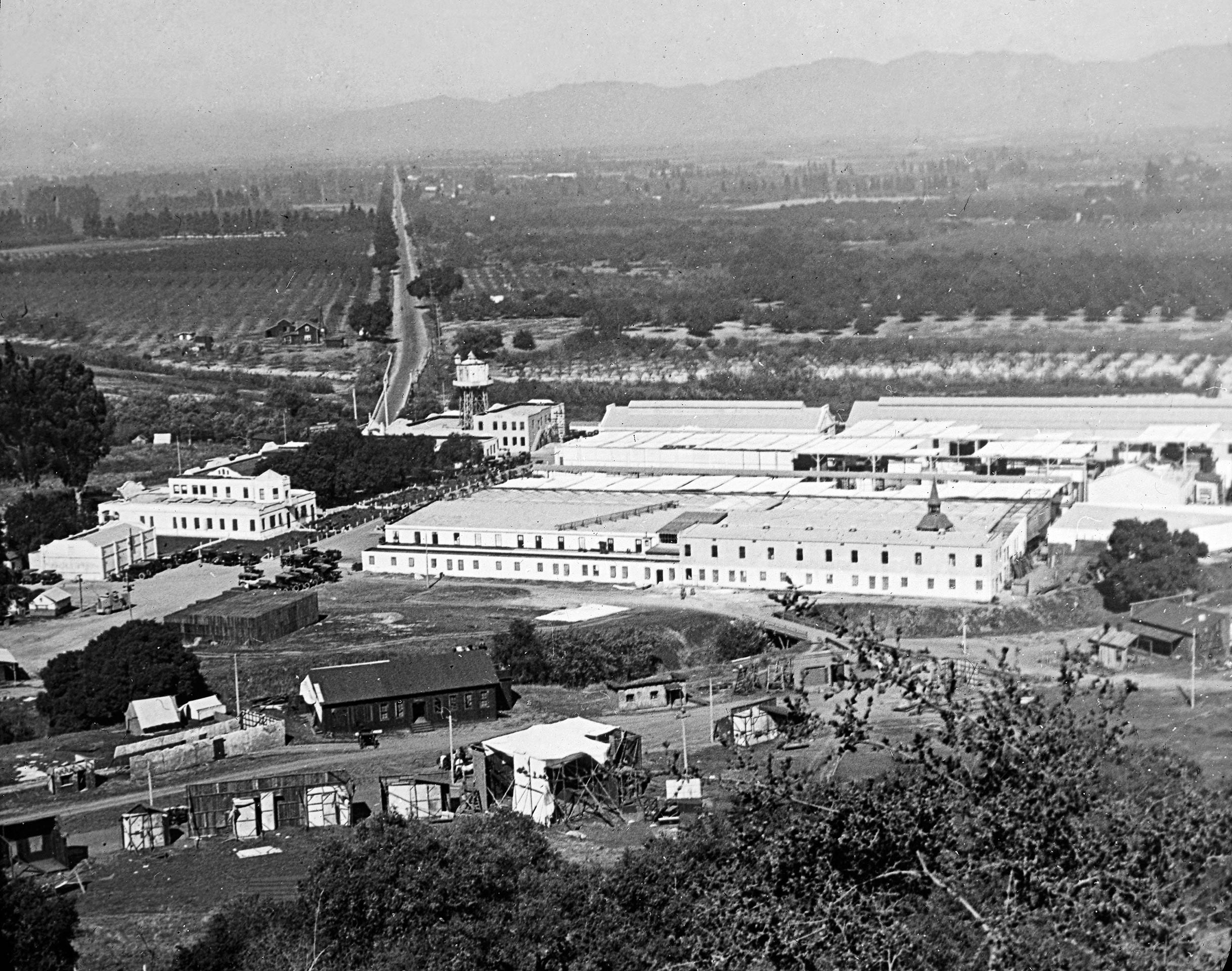

Architects S. Tilden Norton and Frederick Wallach designed the massive project, with construction beginning on June 18, 1914, for a power plant, water supply, sanitation, hospital and infirmary, zoo, bungalows and other facilities, including a gigantic open stage that could accommodate eight film productions shooting simultaneously. Other buildings soon followed: a $25,000 laboratory, $30,000 administration building, dressing rooms, wardrobe building, shops, cafeteria, Indian village and 30 bungalows for employees. The Spanish Colonial administration building even included a stained glass window in the shape of the Universal logo over the front entrance, designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany.

Construction fell behind on what trade publications called the first city constructed specifically for filming motion pictures. Massive rainstorms in early January 1915 flooded the Los Angeles River, causing $130,000 in damage to the studio. Standing sets were swept away, electricity flickered out, streetcar lines washed away and buildings were destroyed. Universal pushed its grand opening to March.

Universal lavishly promoted the studio’s grand opening by purchasing full-page ads in trade magazines and newspapers, urging Americans to attend the celebration for the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” The studio organized an exclusive Chicago-to-Los-Angeles “Universal Special” train trip to attend the celebrations.

The opening extravaganza kicked off at 10 a.m. on Monday, March 15, 1915, with Laemmle presenting a gold key valued at $1,255 to open Universal City’s gate before the studio band played “The Star-Spangled Banner” as United States and Universal flags soared up the flagpoles. City officials welcomed the 10,000 guests. Visitors witnessed stunt shows, a rodeo, an aerial flyover, filming and the flooding of a Western town that swept away sets and reached guest areas.

For everyone else around the country, the company created the one-reel behind-the-scenes film A Tour of Universal City, showing its striking new property and film stars. After opening day, studio visitors paid 25 cents to tour the property, watch filming and eat a boxed lunch.

The growing company blossomed, with the January 1, 1916, Los Angeles Times reporting that Universal City employed 2,000 people and spent $4,000 a day in operating expenses. Unlike most other film studios, the progressive company even featured 11 women as directors, including superstar Lois Weber, considered one of the top three helmers in the industry along with Cecil B. DeMille and D.W. Griffith.

By the 1920s, however, Universal lagged behind most major film studios in revenue because it failed to purchase a theater chain. Though Universal released prestigious pictures like the Erich von Stroheim film Foolish Wives and the horror classics The Hunchback of Notre Dame and The Phantom of the Opera starring Lon Chaney, the company mostly focused on producing westerns and more middle-of-the-road product for rural audiences. Universal staved off bankruptcy after the stock market crashed in 1929, barely hanging on. With the advent of sound, the studio discontinued its tours.

Universal’s well-received horror films of the 1930s, like Dracula, Frankenstein, The Invisible Man and The Mummy, helped keep it afloat for a time before Laemmle was forced to borrow $750,000 in 1935 from Standard Capital to stay in business, giving a purchase option on his personal stock as collateral. In 1936, the company exercised its option, purchasing Laemmle’s shares and forcing him out. It signed teenage singing sensation Deanna Durbin to a contract in March, and the revenues from her films put it back on sound financial footing. The studio once again offered occasional tours to special groups.

Universal changed hands a few times from the late 1940s through the early 1960s, due to technological advances and the Paramount decree breaking up distribution practices. Owners like Decca Records began focusing more on genre pictures and television production. Talent agency Music Corporation of America (MCA), which began diversifying across the entertainment field in the late 1940s, eventually purchased the Universal lot in 1958 to host its massive television production under the name Revue Studios. In 1962, Decca and MCA merged, with the agency gaining control of the new Universal Studios.

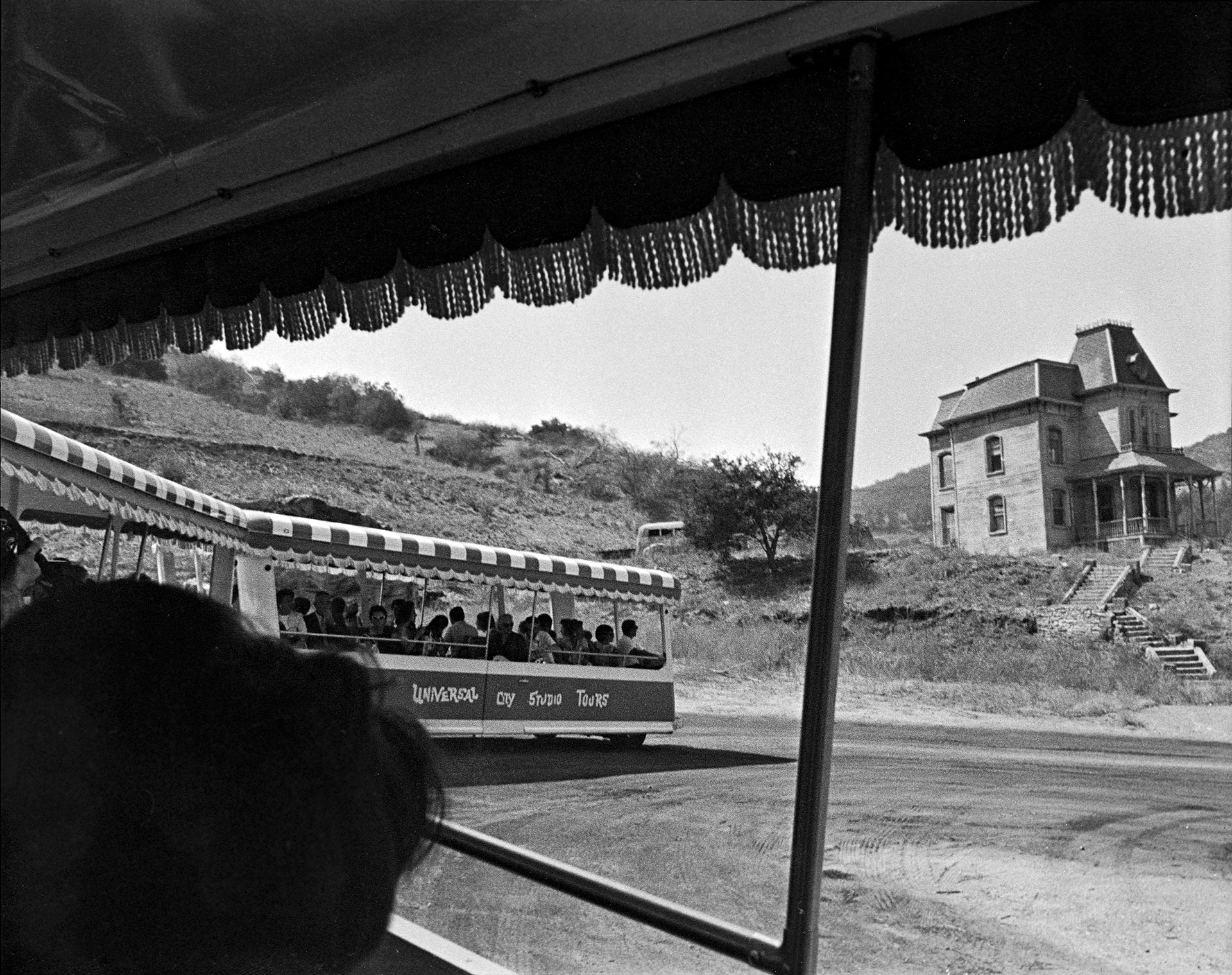

In 1961, studio president Albert Dorskind reintroduced the tour to boost profits to the studio commissary, turning over organization and details to Gray Line Tours. Once Dorskind recognized its profitability, however, Universal took control. Executives realized the value of making it a destination for tourists, allowing them behind-the-scenes access to the studio and giving Universal the opportunity to cross-promote its product and sell souvenirs.

After the loss of the MCA talent agency business and its huge profits in 1964 due to antitrust laws, the new Universal Studio Tour premiered on July 15, 1964, to bring in additional revenue, with a 90-minute tour of the backlot costing $2.50 on colorful open-air trams. Sets from Psycho, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Phantom of the Opera and Frankenstein greeted early guests, who relished the chance to tour an actual movie studio.

To keep tourists and their steady stream of income coming back, the studio upgraded what came to be known as Universal Studios Hollywood, adding a stunt show, animal attraction, the chance to watch actual production and special-effect “surprises” along its route. Eventually Universal introduced characters from its films — such as Bruce the shark from Jaws — to help sell consumer products and studio blockbuster movies, attracting more guests. Enthusiastic fans quickly made it California’s third most popular theme park.

Keeping it fresh to remain competitive and to add value, Univeral continually replaces rides and attractions based on older products with those highighting newer properties, switching out rides based on E.T., Back to the Future, Jurassic Park, Terminator, Shrek, The Fast and the Furious and Despicable Me as new blockbusters grab the popular imagination. Just a few years ago, Universal licensed rights to the Simpsons characters and the Harry Potter series, creating elaborate lands celebrating their entertainment universe.

Hoping to make the park more of a destination hub, Universal constructed hotels, followed in 1993 by developing CityWalk, an outdoor mall of stores, restaurants and movie theaters. Besides attracting tourists, the area serves as a magnet for local residents drawn by its goods and services.

Hoping to make the park more of a destination hub, Universal constructed hotels, followed in 1993 by developing CityWalk, an outdoor mall of stores, restaurants and movie theaters. Besides attracting tourists, the area serves as a magnet for local residents drawn by its goods and services.

Always diversifying, upgrading and refreshing, Universal Studios has survived for more than a century as one of the region’s largest employers, offering diverse forms of entertainment for residents and visitors alike. Universal City has grown and expanded from a simple moving-picture studio into what the company now calls “the entertainment capital of L.A.”