On October 6, 1927, Warner Bros. ushered in the motion picture sound age with the New York City premiere of The Jazz Singer, the first feature film to combine a synchronized recorded music score with sequences featuring synchronized singing and speech. The movie’s massive box office grosses not only saved the studio from financial ruin, but also cemented its aims to develop and promote new technologies. Just a year later, it purchased the First National Pictures studio on Barham Boulevard in Burbank to dramatically increase film production — in effect telling the world, in the words of Jazz Singer star Al Jolson, “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!”

The company had grown out of the ambitions of four risk-taking, sometimes battling brothers who combined chutzpah, intelligence, drive and technical smarts to transform a fledgling exhibition business into one of the world’s greatest film studios. Polish immigrant brothers Harry, Albert and Sam Warner (née Wonksolaser) projected primitive moving pictures in Pennsylvania and Ohio mining towns circa 1900 before purchasing their first film theater in 1903. The go-getters founded the Pittsburgh-based Duquesne Amusement and Supply Company in 1904 to distribute moving pictures and were producing their own films by 1917, now joined by baby brother Jack.

Leasing the Burston/Horsley Studio on Sunset Boulevard in 1919, the Warner brothers entered Hollywood film production for the first time. Exploding in size while ballooning its debt, the neophyte company added a Warner Sunset Studio, radio station KFWB, the Vitagraph Company and experimental sound pioneer Vitaphone over the next several years, leading the industry’s technological growth. Technically-minded brother Sam determined proper amplification and perfected synchronized recording between film and the Vitaphone disks, leading to the monumental success of The Jazz Singer. Unfortunately, Sam died of a cerebral hemorrhage on the West Coast the day before the film’s premiere.

With Warner Bros. now financially stable, oldest brother and president Harry purchased the Stanley Theatre Company in September 1928 to ensure wide distribution of their titles. In October, he bought two-thirds of First National Pictures, a large film producer–distributor, gaining its two-year-old Burbank studio in the process.

Los Angeles film theater czar Thomas Tally and J.D. Williams had established First National in 1917 as a circuit of independent motion picture exhibitors who began purchasing films on their own. In 1922, they bought United Studios on Melrose (what is now Paramount) to produce their own product. Looking for a large but affordable piece of property on which to grow, the company purchased 68 acres from farmer Howard G. Martin, located adjacent to the Los Angeles River on the original Dr. David Burbank Rancho Providencia Tract, which production executive Richard Rowland called “a perfect setting for a studio.”

Construction commenced March 28, 1926, on the $1.5 million Austin Company–designed Spanish colonial revival production plant. A 600-man crew worked around the clock erecting the 350,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art studio, finishing by June 15. As Rowland later stated in a special section of the September 11 Motion Picture News, “In laying out the plant at Burbank the effort was made to build a model studio — one that would take advantage of everything which our own experience indicated was necessary.” Amenities included an emergency hospital, a pool, a portrait gallery and studio department, a fire sprinkler system, landscaping, a schoolhouse, tennis courts and an elaborate dressing-room building.

When it opened, the studio created an eye-catching four-page brochure entitled “First National Studio — the Greatest Studio on Earth,” boasting of the facility’s six “mammoth stages,” 27 buildings and an electrical power plant producing 33,000 volts of electricity, enough to supply a city of 15,000 people. When Warner Bros. acquired the location, it consolidated its production by moving all filmmaking to the Burbank facility and gradually building an elaborate backlot.

Warner Bros. continued experimenting with technology as well, helping popularize Technicolor with its color-drenched 1930s musicals and advancing sound with its Vitaphone shorts and action pictures. The studio formed Warner Bros. Music after acquiring a string of music publishers, soon purchasing Brunswick Records to help distribute product and buying radio companies to market and popularize its releases. It also popularized snappy animation with the Leon Schlesinger–produced “Looney Tunes.”

Adjacent neighborhoods in Toluca Lake and Burbank quickly expanded as studio employees bought homes near their work. Many Warner Bros. stars took up residence in Toluca Lake, drawn as much to its warm, hometown feel as its location near the studio. Local businesses flourished as well, gaining much-needed new revenue, particularly during the challenging Depression. Nearby Lakeside Golf Club evolved into the studio’s unofficial clubhouse, with many stars taking lunch breaks to hit a few golf balls or eat in luxurious privacy.

Warner Bros. films attracted high box office receipts over the next few decades, popular with American audiences looking for a respite from challenging finances or enjoying socially realistic commentary on topical issues of the day. Its movies featured tough-talking, unconventional-looking stars with magnetic, larger-than-life personalities like Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck and Humphrey Bogart, starring in everything from snappy pre-Codes to Busby Berkeley–directed musical extravaganzas to topical, action-packed gangster pictures to swashbuckling epics. In the 1940s, Warner Bros. produced classic films recognized as integral parts of Americana, like Michael Curtiz’s romantic, patriotic Casablanca and flag-waving Yankee Doodle Dandy, John Huston’s world-weary film noir The Maltese Falcon and Howard Hawks’ evocative The Big Sleep.

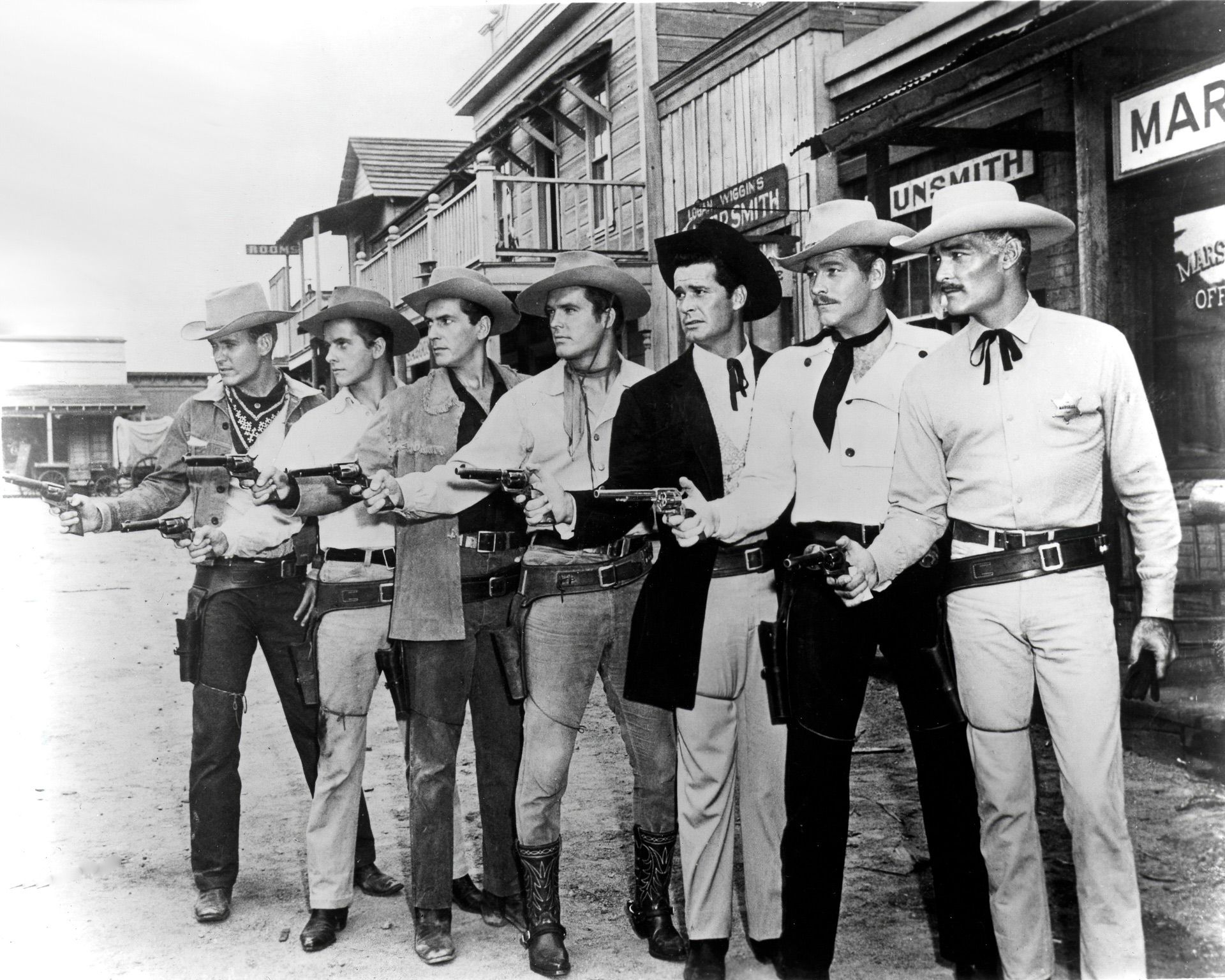

In 1948, the Justice Department’s antitrust case, United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., forced studios to divest themselves of their theater chains. Warner Bros. shrank its production slate and reduced staff. Just a few years later, the popularity of television dealt a second body blow to the studio. Warner Bros. continued belt-tightening, further cutting movie production to focus on producing big-budget spectacles. Seeking ways to increase revenue, the studio once again looked to new technology, producing 3-D films and employing widescreen processes like CinemaScope to differentiate itself from television fare. It opened Warner Bros. Television in 1955, producing hit westerns like Maverick and detective shows like 77 Sunset Strip.

The 1950s continued to bring rising challenges to the studio. It spun off its theater holdings as Stanley Warner Theatres in 1953, which soon merged with RKO’s distribution arm. It also sold off most of its catalog of shorts and pre-1950 films to television in early 1956. Later that year, the three Warner brothers announced they were selling the studio. Younger brother Jack secretly joined Boston banker Serge Semenenko’s syndicate, which purchased 90% of the family’s stock before Jack bought back his own, becoming the new studio president in the process and destroying his relationship with his brother Harry.

Jack Warner later sold out to Seven Arts Productions in 1966. Just two years later, however, Seven Arts accepted a cash and stock option offer from Kinney National Company, reverting back to Warner Bros. Inc. Looking for more financial relief, CEO Ted Ashley moved further into co-production deals with stars and negotiated with Columbia Studios in 1971 to form Burbank Studios, Inc. The two combined below-the-line staff and production facilities at the old Warner Bros. lot and shared Columbia’s old movie ranch off of Hollywood Way.

Looking for additional revenue, Burbank Studios opened a tour department to public guests in 1973. While celebrities and Warner Bros.–connected business owners had enjoyed special lot tours beginning in the 1940s, the company now focused its efforts on building relationships with film fans and local residents and introducing upcoming shows. Warner Bros. intentionally kept tours small and focused on actual production to differentiate itself from neighbor Universal Studios’ staged thrill-ride showpiece.

Former mailroom employee Dick Mason headed the new department, which featured guides leading intimate groups on spontaneous walks around the lot to examine the production process, watch the shooting of an actual show and visit vintage sets, backlot locations and film departments. Newspapers called it the tour for more serious film fans, offering the most realistic look into a modern entertainment studio that showed “how things are really done.”

The tour evolved into a more commercial endeavor over time, gaining the name VIP Tour. By the early 1990s, it expanded to two hours and featured film clips, along with driving guests around in carts. Warner Bros. even added a 10,000-square-foot museum in 1996 to display pop-culture artifacts and historic information. In June 2021, the studio celebrated a grand reopening of the tour with brand-new immersive experiences centered on some of its most popular properties, including Friends, the world of DC superheroes, and the Harry Potter and Fantastic Beasts movies.

Through the last few decades, the venerable studio lot has passed through a few owners’ hands, all involved in various new forms of technology but recognizing the beauty and historical significance of the property. Community outreach deepened, with neighbors occasionally invited to open houses, street fairs and other special events. While entertainment continually evolves, the studio remains a steadfast part of the industry and an enduring local landmark.

For more details about the newly revamped Warner Bros. studio tour, check out our bonus story, “A Local Tour Through Entertainment History.”