Whoomp, whoomp, thud! My butt hit the mud as my horse, a beautiful young palomino colt named Golden Rule, once again, as he always did, threw me into the muck and sand of the old Los Angeles River. I was a good rider, taught by the best, but I had almost never ridden my colt alone without getting thrown at least once. It seemed to me that a nefarious plot was working against me, and I might have been right.

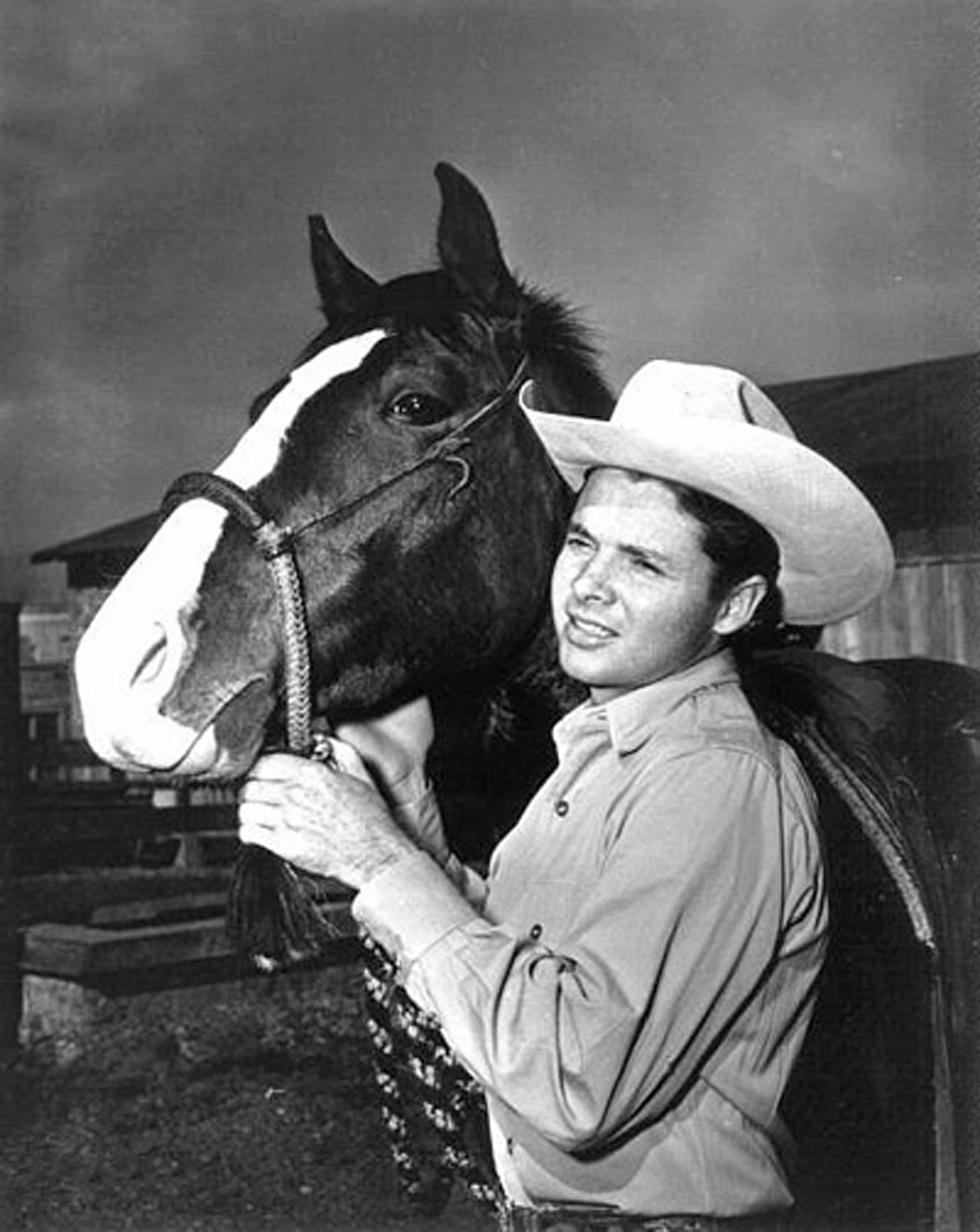

All the facts regarding how I acquired the colt have never really been known, and they may never be. As the story grew over the years, Wild Bill Elliott lost him in a poker game to Sonny Tufts at my house in Toluca Lake one Saturday in the ’50s. Not having a place to keep him, Sonny traded the yearling on the spot to either Audie Murphy, Ward Bond or writer/director Burt Kennedy for a beautiful Mossberg over-and-under 12-gauge shotgun that Sonny coveted. Whoever did the trading missed one small but important detail: The shotgun in question was hanging over the fireplace in my parents’ game room. Needless to say, it belonged to my dad, who at that moment was on his way home from sorting out a problem on a western movie shoot in the mountains of Lone Pine, California.

The rotgut haze had lifted by the time the missing shotgun was noticed. Apparently, true to the sacred code of these Three Musketeers, neither Audie, Mr. Bond nor Mr. Kennedy would readily admit to the deed. So, somehow, true to this same code, I ended up with Golden Rule, the Horse From Hell, and the shotgun once again hung in its proper place. Because of the events that followed, I always felt Audie was the verysavvy horse trader who obviously recognized this devil in horseflesh.

Audie Murphy had been born in Kingston, Texas, on June 20, 1925. He was raised in a sharecropper’s dilapidated house. Audie’s father deserted the family in 1940, and his mother passed away a year later. Moved to do something to honor his mother’s life, Audie enlisted in the military 10 days after his 17th birthday, falsifying his birthdate to make himself appear a year older to meet the age requirement. In February 1943, he left for North Africa, where he received extensive training.

A few months later, his division moved to invade Sicily. His actions on the ground impressed his superior officers, and they quickly promoted him to corporal. While fighting in the wet mountains of Italy, Audie contracted malaria. Despite such setbacks, he continually distinguished himself in battle.

In August 1944, his division moved to southern France as part of Operation Dragoon. It was there that his best friend was lured into the open and killed by a German soldier pretending to surrender. Enraged by this act, Audie charged and killed the Germans who had just killed his friend. He then commandeered the German machine gun and grenades and attacked several more nearby positions. Audie was awarded the first of several Distinguished Service Crosses for his actions.

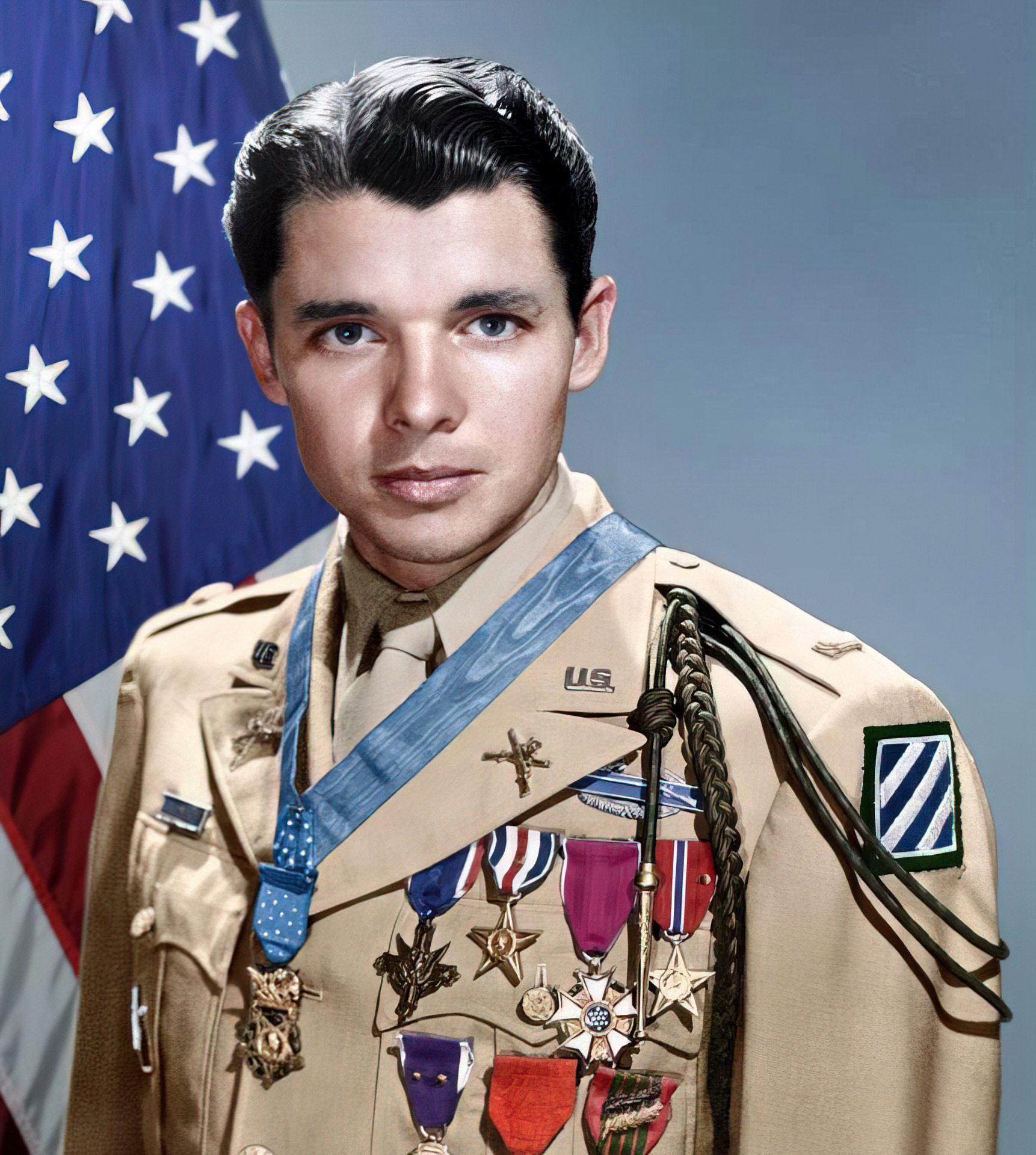

Over the course of World War II, Audie witnessed the deaths of hundreds of fellow and enemy soldiers. Endowed with great courage in the face of these horrors, he was awarded 33 U.S. military medals, including three Purple Hearts and the Medal of Honor. He became the most decorated combat soldier in American history.

In June 1945, Audie returned home from Europe a hero and was greeted with parades and elaborate banquets. LIFE magazine honored the brave, baby-faced soldier by putting him on the cover of its July 16, 1945, issue. That photograph inspired actor James Cagney to call Audie and invite him to Hollywood to begin an acting career.

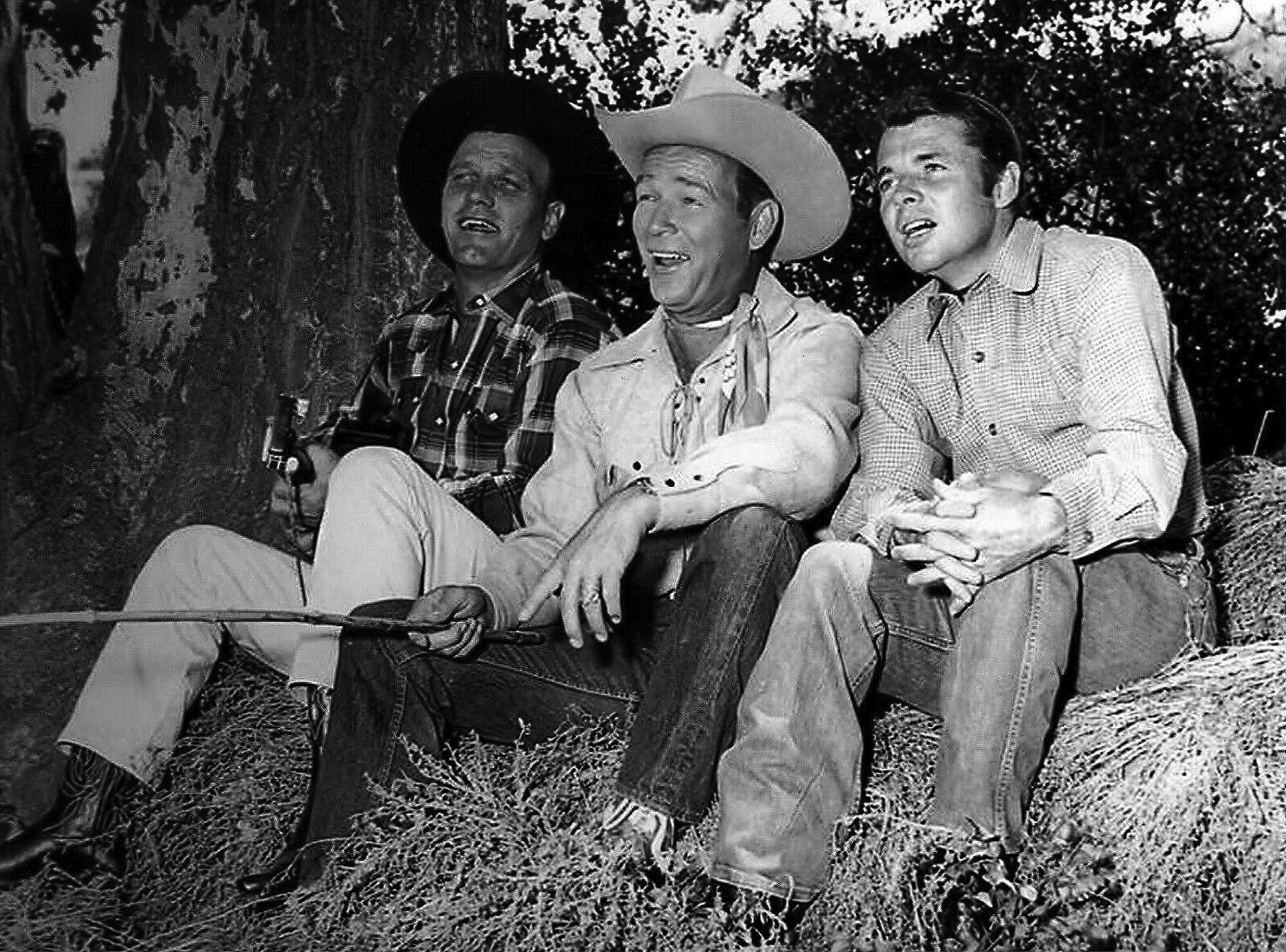

In 1949, Audie published his autobiography, To Hell and Back. The book quickly became a national bestseller, and in 1955, after much inner debate, he decided to portray himself in the film version of his book. The movie was a hit and held Universal Studios’ record as its highest-grossing motion picture until 1975. Murphy would make 44 feature films in all, mainly westerns. In addition to acting, he became a successful country music songwriter, and many of his songs were recorded by well-known artists, including Dean Martin, Jerry Wallace and Harry Nilsson.

Audie lived a few blocks away from me on Toluca Road and had a small barn on his property. My school chum, Peter Meyers, lived next door to Audie, and he and I would hunt mice in the barn with our trusty Red Ryder BB guns. (Mine was “borrowed” from Peter’s older brother, because my mom wouldn’t let me have one.) Audie paid us 10 cents a mouse, which we figured was the going rate at the time. We could do better selling golf balls that were scrounged from Lakeside Golf Club’s water hazards and over the fence on Valley Spring Lane for a quarter a ball. But we wouldn’t get to hang out with Audie and his lovely wife, Pamela, who made great tuna sandwiches! Easy choice.

To pay for Golden Rule’s boarding fees at the small ranch at the end of Chiquita Street owned by my orthodontist, Dr. Van Meter, I cleaned the stables on weekends after I had my braces tightened. The doctor’s ranch and dental office was about halfway between Universal Studios and Republic Pictures. A trail led down to the old Tujunga Wash, which ran into the L.A. River beside both studios. Each studio had an earthen berm that could be ridden up onto the studio property from the river bed. In those days, if you ever wanted to see cowboy movie stars from either studio, the riverbed was the place to be. This was as the cement ditch we now call the L.A. River was being built. At the moment, the construction was making its way from around Sepulveda Boulevard to the ocean. Sadly, our crawdad-catching stream would soon be gone.

A month or so later, my dad, Audie — who boarded his horse, Flying John, with the good doctor — and Dr. Van Meter himself all decided it was time to geld the palomino, and I drew the short straw. Has anyone ever noticed that when you’re a kid and dealing with grownups, all the straws are short?

While the adults held Golden Rule, I mimicked a scene I had witnessed in fascination many times. A quick slash with an oddly curved knife, a whack in the vacated area with a hot tar brush amid a flurry of flashing hooves, and the deed was done. It escaped my attention, as I was causing the colt to lose his stallion-hood, that the Horse From Hell was looking me right in the eye. Events to follow proved elephants aren’t the only animals that never, ever forget.

It was also decided, because it was my horse, that I would have the great pleasure of saddle-breaking the young colt. Much to my surprise, it all went very well. This was all part of the Devil Horse’s evil plan! Within a week or so, it was obviously time to ride over to Republic Studios, show the wranglers my handiwork and surprise Dad, who was the comptroller at the studio.

At almost exactly the point of no return in the riverbed, and also the only really deep and rocky area for miles, the colt threw me in the water like a dead tick and raced back to the barn. Dazed, I picked myself up and tried to decide what to do: Start walking to the studio and face the jeers of the heroes of my youth, or go back to the ranch and kill and eat the horse … no contest. But, by the time I got back to the barn, I was so wet and miserable, I forgot about the vendetta.

The dreaded “Get right back on” syndrome took effect, and for days, weeks and seemingly eternity, I tried in vain to ride the whole way to the studio. Short of tying myself to the saddle horn, I could never stay on board. Now, here’s when the Horse From Hades’ devilment really started. My dad and Audie, who was probably feeling a bit guilty, but genuinely concerned, offered to ride along and see what on earth I was doing wrong. Yep, nothing ever happened, that horse rode like he was in the Rose Parade. Back at the barn, hoping for a miracle, I thanked them both for all their advice and kindness. But the very next time the colt was alone with me, wham! And it never got any better!

Sadly, there is no happy ending to this saga from perdition. Eventually, Dad sold the horse and “put the money in the bank” for me. Years after both Dad and the steed from blazes were in cowboy heaven and horse hell, respectively, I realized that darn animal was still doing it to me. Sometimes, in the still of the night, my wife will try to wake me as I shout over and over, “Dad, Dad, which bank, which bank?”